Inclusive communications. This is a term we are already seeing more frequently in our projects and communications or PR processes. It has taken the form of sign language interpreters like B.C.’s very own Nigel Howard, an ASL interpreter who now has his own fan club because of the pandemic, or closed captioning on social media for infrastructure projects in Metro Vancouver.

Now is the right time to ask ourselves: How can we bridge the gaps between the hearing and non-hearing communities, and improve communications with the Deaf/Hard of Hearing, and by extension, the disability community in general? With the willingness and leadership of the communications and PR industries, we can successfully communicate with a community that has long been overlooked and underserved in our province.

Why do we need more inclusive communications?

Every stakeholder in our community deserves to be informed and it's important to think about those we don't normally consider (go the extra mile!) to give them opportunities to participate and be fully engaged.

Including people with disabilities in general, and in this case the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, greatly enhances every communications and engagement efforts and the reputations of the organizations we represent. Millennials today in particular, want to see brands and organizations that reflect diversity and inclusion. We begin to remove barriers to access and inclusion simply through enabling these inclusive communications tools and practices.

Identifying the needs before meetings, events, and consultations

There is no cookie cutter solution for inclusive events. Some may require a sign language interpreter, some require both captioning and an interpreter, and some require captions only but may wish to have summaries or minutes to refer to afterwards. How can we tell? For every event or meeting, it is best to ask for the preferences in advance if possible. As part of pre-event planning, the best bet is to ask on event registration forms and using checklists such as UBC’s inclusive event checklist so that planned events and conferences can contain an option for attendees to discreetly disclose at registration.

An upcoming AGM for Accessible Standards Canada has a great example of an inclusive registration form you might use as inspiration for your upcoming events.

Social media for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

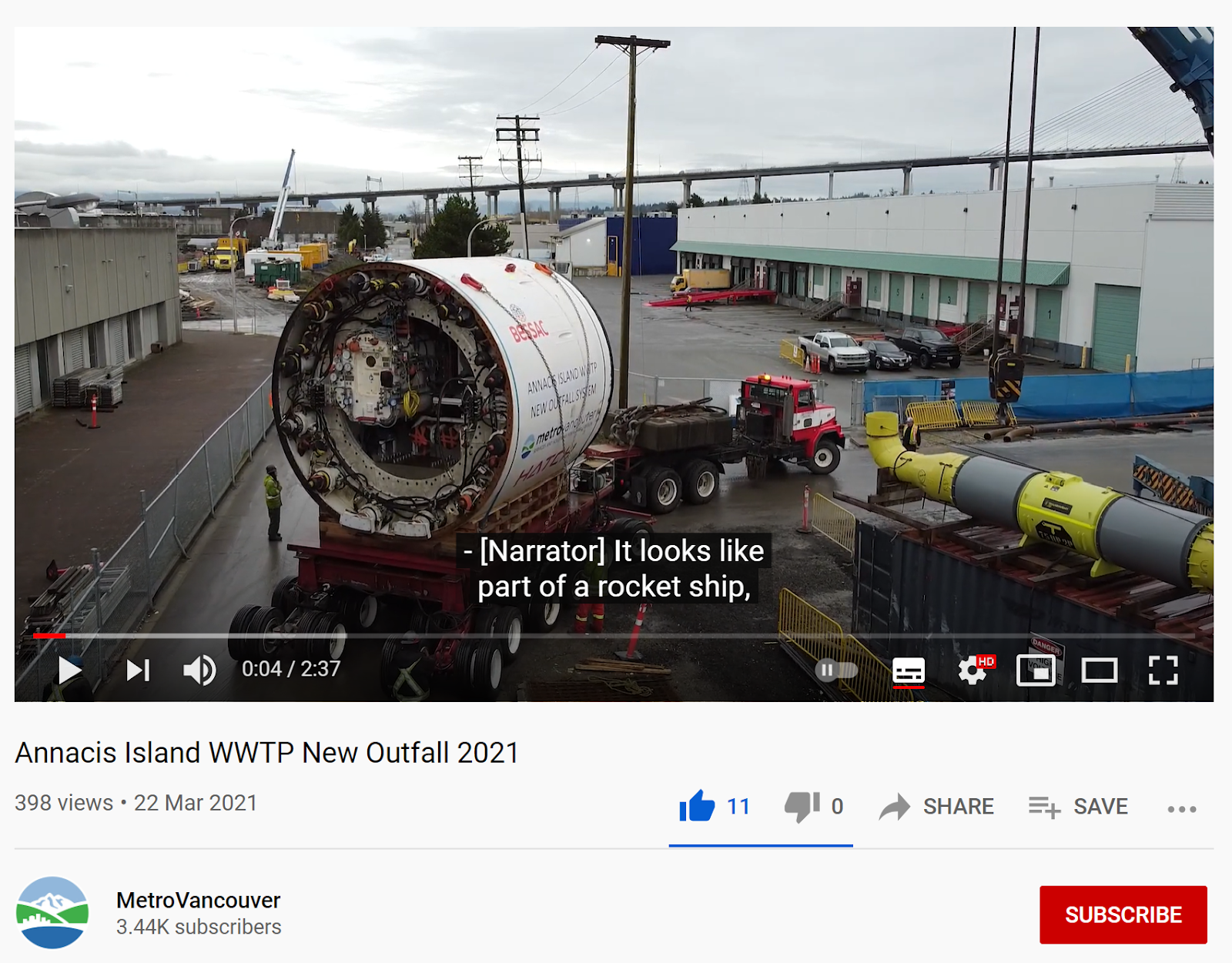

We have also seen a rise in social media captioning and accessible text. It's important that we ensure social media is accessible; it not only boosts engagement and viewership, but it retains and grows your audiences. Social media and digital communications professionals understand that it improves SEO too as having captions helps improve your visibility and overall engagement experience. It is important to understand that having captioning or videos in sign language is the primary means of receiving information, and often it can mean a life threatening difference in certain situations, like getting important pandemic health information. Some examples include the Provincial Health Services Authority’s pandemic virtual town halls in both sign language and with captioning, embedded captions on Translink’s IGTV videos, and examples from the Presidents Group.

The Provincial Services Health Authority has been organizing virtual townhalls for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community, delivering in both closed captionings and with a sign language interpreter.

Translink has incorporated the embedding of captionings into its vertical IGTV videos on Instagram, and included it into the other major social media platforms.

The Presidents Group also offers tips on how to caption your meetings and videos that benefit everyone, not just the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

Avoiding assumptions and language pro-tips when interacting with the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

How you use certain words or gestures can make or break your inclusive communications efforts, it's best to start from a point of empathy and a positive-language focus:

-

Be open-minded, start by asking what's best to communicate with the individual and don't assume it's the same for everyone—it can lead to unconscious biases

-

Slowing down the pace of your speech is the easiest change you can make, and can be extremely helpful. It reduces the chances of missing what is being said, and also allows captioners to keep up.

-

Turn-taking is crucial: one speaker at a time, especially in group settings. Multiple simultaneous speakers or people talking over each other can make it impossible for Deaf and Hard of Hearing individuals to understand.

-

At in-person or virtual events, some may or may not be comfortable speaking about their disability including their assistive technological devices, so when in doubt, ask with a positive and empathetic mindset. (i.e., "How can I help make your experience better today? What is your preferred communication mode? I really like your hearing aids/cochlear device, they're pretty cool! How do they work?")

-

Avoid direct questions and obvious statements like, “You don’t seem deaf to me” or “How come you speak so clearly?” or even the odd, “Do deaf people drive?” It is important to note, many in the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community have faced a significant amount of life challenges and adversity to meet society’s expectations—and continue to do so. Such language can be perceived in a much different light despite one’s positive intentions.

-

If you are truly curious, gently ask the individual to chat in a casual setting, perhaps over coffee or tea. Deaf and Hard of Hearing individuals are ultimately the experts on themselves and their needs.

-

Ensure to follow up personally and see if anything is needed after the event ends, or if the individual was able to fully participate. Some require a feedback loop.

-

Being Deaf or Hard of Hearing knows no boundaries, age, ethnicity, nor gender. It can happen to anyone, whether since young, through various circumstances, or into the later stages of life.

-

If you make a mistake, it’s okay to keep learning to be more inclusive together! The objective is to ensure we are on a journey of learning and growth together. We are all human after all!

For more information for community resources and the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community visit these links:

The difference between d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing

You may have noticed that in this blog the term “Deaf and Hard of Hearing” has been used throughout. This is the most commonly accepted term currently in use to describe this community. Small variations do exist, but for the purposes of universal acceptance, this is the best term most can agree with at this point in time.

For starters, ‘Deaf’ refers to the culturally Deaf, a cultural identity for people with hearing loss who share a common culture and who often have a shared sign language. People who identify as Deaf often prefer to use sign language and it may be their first language, and they may not see themselves as having a disability.

Lowercase ‘d’ in ‘deaf’ refers to those who have a physical condition of hearing loss. Not everyone who identifies as ‘deaf’ uses sign language, they may come from a hearing family, they also may or may not identify with the Deaf culture, and hence the reason to not make assumptions as mentioned above.

‘Hard of Hearing’ refers to those who may have mild to severe hearing loss, and with the assistance of an auditory device such as a hearing aid, may be able to process speech. They too may or may not identify with Deaf culture in general.

This community is so diverse, and so are the viewpoints when approaching this topic. It is important to understand that there are different lived experiences, and so the emphasis is more on the attitudinal rather than the terminology itself when interacting with the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, but also taking their identities into account as well.

Accessibility legislations

In the last couple of years, consecutive federal and provincial governments have either introduced, begun consultations, and/or passed legislation that enables accessibility to be a greater part of the public policy-making, consultations, and decision-making considerations. Communications, information and communication technologies are considered essential to removing barriers to access. Organizations like the Greater Vancouver Association of the Deaf (also known as DeafBC) are stakeholders in ensuring closed captioning and ASL interpreters are part of the requirements in accessibility standards. For a full list of tools and resources, see below.

Tools and resources to get you started

Technological advances in recent years now allow the Deaf and Hard of Hearing individuals to begin fully participating in all aspects of their lives. Here are some tools we can use in future events, both online and in-person:

-

Event or in-call captioning solutions: Affordable options, such as Otter.ai for Zoom, Webex Assistant, Web Captioner, and the more precise Live-event C.A.R.T. captioning (also known as short-hand captioning).

-

Social media captioning: Accessible captioning includes built-in, editable captioning for Youtube, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

-

Sign language interpreters may be readily available to assist, whether employed by public authorities, or through a community of sign language interpreters and non-profit support organizations such as the Wavefront Centre for Communication Accessibility (formerly the Western Institute for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing).

-

Video Relay Services: If your organization has a front desk, chances are a deaf or hard of hearing person may wish to call directly. Relay services enable deaf and hard of hearing individuals to communicate in a manner that is as close to “functionally equivalent” as possible to the communications enjoyed by telephone users. Major telephone providers have relay services available, and the CRTC offers guidelines around such services.

-

Telecoil loops (or induction loops): This type of technology converts sounds into an electromagnetic (EM) field that can be picked up by personal amplification devices, such as hearing aids, bone anchored hearing aids, or cochlear implant processors that are equipped with a telecoil (or t-coil). They are most useful for meeting rooms, reception spaces, auditoriums, bars and pubs, as well as any space that requires a sound system.

-

Learning sign language: If you are feeling adventurous, both Vancouver Community College’s ASL Program and UBC's American Sign Language program are available so that anyone can start learning.

-

AI-powered live transcription apps for mobile phones when you are on the go include Live Transcribe for Android, Otter.ai for Android and iOS, etc.

Inclusive communications means bridging the wide gaps that exist between the hearing and the non-hearing communities because helping build an accessible future post-pandemic, where all feel included and welcome in any setting based on dialogue, compassion, and empathy.

“To communicate the truths of history is an act of hope for the future.” - Daisaku Ikeda

The author would acknowledge the participation of Charles Fontaine, Registered Audiologist, and Rytch Newmiller, M.S.W., both of Wavefront Centre for Communications Accessibility for their expert reviews of this blog.

About the Author

Gent Ng is a multi-faceted communications professional and digital storyteller who has weaved through various government and private sectors. With more than 15 years of active related volunteer work with several non-profits and community organizations in various communications and stakeholder-related roles, he is curious by nature, but driven by how storytelling can impact our communities in both new and existing mediums. He is a person with a life-long disability, and hopes this blog will advance the inclusion of people with disabilities in public relations and communications.

Gent Ng is a multi-faceted communications professional and digital storyteller who has weaved through various government and private sectors. With more than 15 years of active related volunteer work with several non-profits and community organizations in various communications and stakeholder-related roles, he is curious by nature, but driven by how storytelling can impact our communities in both new and existing mediums. He is a person with a life-long disability, and hopes this blog will advance the inclusion of people with disabilities in public relations and communications.

Gent holds a B.A. in Political Science from SFU and a Diploma in Digital Marketing from UBC Sauder School of Business. When Gent needs a break, he can be most commonly found exploring culture and architecture in neighbourhoods with a cup of coffee in hand or chasing sunsets with a camera.